EU defence procurement operates under the framework of the 2009 Defence Procurement Directive. This Directive established common rules for the procurement of defence and sensitive security related products, services and works across the EU. It can apply to conventional defence as well as more modern forms of defence such as cyber defence.

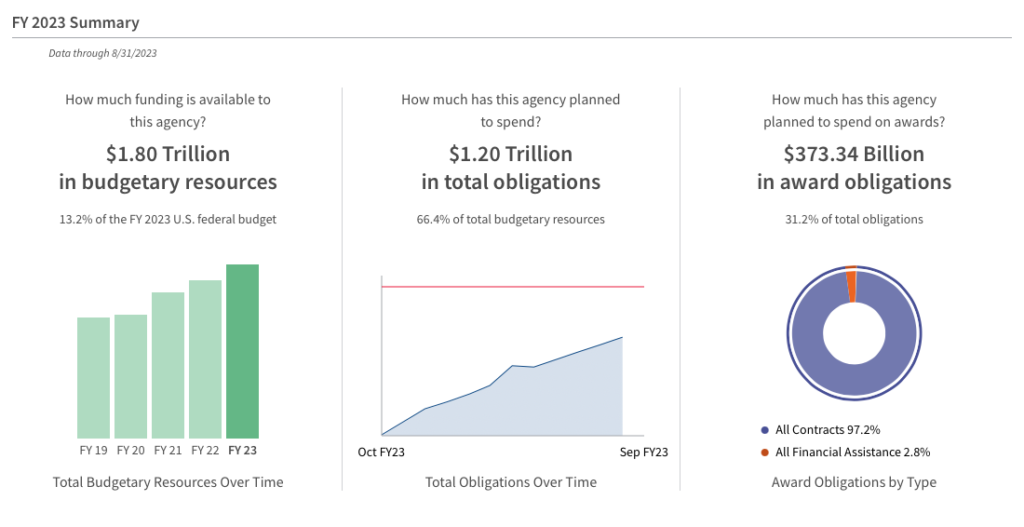

The United States has a voted expenditure of USD 1.8tn which is more than the entire public procurement market in the EU. It expects to spend USD 1.2tn. By contrast, the estimated 2023 expenditure across in the EU on defence was measured at EUR 214bn by the European Defence Agency in December 2022. The EDA comprises 27 members of the EU and it works to improve the effectiveness of defence in Europe across disparate systems and priorities.

Note: The United Kingdom continues to have the largest defence spending in the continent Europe (ex Russia) but is not included or addressed in this article as it is not a member of the European Union and this article is focused on EU procurement and comparisons with the system in the USA.

The directive only applies to expenditure over the amounts specified in Article 8 of the directive. This is broadly aligned with the utilities directive of 2014. Goods and Services contracts worth over EUR 431,000 and works in excess of EUR 5.382m are captured by the directive. Below this threshold, more flexible rules apply.

The same general principles familiar to EU procurement professionals from the classic, utility or concessions directives of transparency, non-discrimination, and equal treatment also apply to this directive. It is intended to encourage open competition as well as fair and transparent procedures. An e-tendering platform is meant to be used to advertise, distribute documents, and facilitate the tendering process. Above these thresholds, contract notices are published in the Official Journal of the European Union (TED, Tenders Electronic Daily). Over 300 databases across the EU feed into the OJEU platform, TED. Potential providers across the World Trade Organisation, that are parties to the agreement on government procurement (GPA) with the EU are also eligible to bid on these tenders. The suppliers check key codes called common procurement vocabulary codes. These codes help suppliers understand when an opportunity presents for them.

The directive outlines various procurement procedures that can be used. These include open procedures, restricted procedures, competitive dialogue, negotiated procedure with prior publication, and innovation partnerships. The specific procedure selected should be determined by the nature and complexity of the procurement. The more technical and cutting edge the equipment, the more likely a procedure like competitive dialogue will be used. For routine procurement, an open process or even something procured by a central purchasing body may be leveraged. Regardless as to the approach taken, contracting authorities should be judicious in selecting the right approach. There is an active case at present between Germany and Finland relating to a direct award. Readers can decide for themselves whether they believe the complainants (Heckler and Koch of Germany) have a stateable case.

Evaluations have to be as objective and transparent as they are in any other process. It is common for appeals and litigation to ensue in defence procurement given the sums of money that can be involved. For instance, the Air Search and Rescue service contract has been subject to litigation following an award in Ireland in 2023. The value of this contract is EUR 800m over ten years. The total defence budget in Ireland is EUR 1.23bn (2023) – approximately 0.2% of GDP. The risk of litigation following awards puts a heightened obligation on contracting bodies to ensure technical specifications are clear and marking is proportionate. Large differentials in marks should not be awarded for bells and whistles if an item is functionally serviceable. Differences can be afforded that are proportionate to the core utility / value being derived from what is being purchases. Explanations around differences need to be objective and as empirical as possible. Failing to do this, can lead to very costly errors.

Due to the sensitive nature of defence procurement, there are provisions in the directive to protect classified information and ensure the security of sensitive materials and technologies. While this matters a lot for conventional defence procurement, it is particularly important for countering cyber warfare. This can have an impact on competitiveness and who regimes buy from. The overlapping nature of NATO, the Five I’s alliance (USA, Canada, UK, Australia and New Zealand), EU membership and other alliances means that military and political power do not always align. While the US are an ally, they are also a rival. So are Australia and New Zealand. France and Germany frequently disagree (for instance), over buying US military hardware.

The directive provides a framework for legal remedies for suppliers who believe they have been unfairly treated during the procurement process. This includes the ability to challenge decisions through administrative or judicial procedures. The most high-profile dispute in recent years relates to the AUKUS submarine dispute between France and Australia (which drew in the Americans and the UK who benefitted from the change of contract provider). The cost of exiting the contract is over EUR 500m.

Defence procurement differences with the United States

Defence procurement in the European Union (EU) and the United States have similarities but have key differences also.

In the EU, defence procurement involves multiple member states with varying defence priorities, resulting in a more fragmented market. Each country often has its defence industry and procurement policies. In the US, defence procurement is centralised under the Department of Defence (DoD), leading to a more unified approach. The European Defence Agency is meant to enhance cooperation, but it is in its infancy. The EU also has constitutionally neutral members like Austria as well as small countries like Malta and Ireland that do not prioritise strategic military defence investment compared to other members of the EU. Malta spends EUR 87m on its defence annually (2022).

The US defence industry is dominated by a few large companies, although it includes numerous smaller suppliers. In the EU, the defence industry is more diverse, with several major defence companies in different member states and close neighbours like Switzerland and Israel.

Both the US and the EU emphasise technology and innovation in defence procurement. However, the US has historically invested heavily in research and development, leading to numerous cutting-edge defence technologies and systems. Israel’s iron dome missile defence system is supplied by the United States. The US currently outspends the EU by a factor of between 6:1 and 9:1.

The US works closely with European countries on defence and security matters (primarily through NATO). The EU, however, is increasingly developing its security and defence initiatives, such as the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and the European Defence Fund. Both the EU and the US have export control regulations governing the sale of defence products to foreign entities. However, these regulations can differ in their approach and specific requirements. For instance, Russia had an order for two Mistral helicopter carriers cancelled by France in 2015 following its annexing of eastern Ukraine.

Key weaknesses in EU defence procurement

Several weaknesses in the EU defence procurement have been identified, impacting the efficiency, competitiveness, and effectiveness of defence acquisitions. These include:

- Fragmentation and Duplications: The defence procurement market in the EU is fragmented because each member state does its own thing. This leads to duplication of efforts, increased administrative burdens, and reduced economies of scale, hindering collaborative and efficient procurement.

- Lack of Standardisation: The absence of standardised procurement procedures across the EU member states results in varying regulations, documentation requirements, and selection criteria. This complicates the process for companies operating across different EU markets and increases the risk of litigation.

- Complexity and Lengthy Procedures: The procurement process is often lengthy and complex due to bureaucratic hurdles, intricate legal frameworks, and differing national rules. This increases the cost and time required to complete procurement cycles.

- Limited Transparency and Access: The lack of full transparency in the procurement process inhibits fair competition and equal opportunities for companies to participate, particularly for smaller or non-domestic suppliers.

- Limited Collaboration and Pooling of Resources: There is a lack of effective collaboration and pooling of resources among member states, resulting in missed opportunities for joint development and acquisition of defence equipment, leading to inefficiencies in terms of cost and capability.

- Reliance on Traditional Players: The defence market in some EU countries is dominated by established defence companies, limiting competition and potentially hindering innovation and the introduction of new, more cost-effective technologies and solutions.

- Cybersecurity and Emerging Threats: The evolving nature of security threats, especially in areas such as cybersecurity and hybrid warfare, requires adaptability and agility in procurement processes, which might not be fully integrated into traditional defence procurement frameworks.

- Barriers to Entry for SMEs: Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face challenges entering the defence market due to high entry barriers, including complex regulations, certification requirements, and limited access to information.

In summary, EU defence procurement rules are clear and quite close in nature to classic and utility directives. As long as reasonably diligent contracting authorities take the time to select the right process and respect the procurement principles, processes should deliver compliant outcomes.

This said, procurement processes will occasionally rub against geopolitical priorities. Non-procurement related considerations (realpolitik) are often at the heart of military procurement friction.